‘Memory’ is a label for a diverse set of cognitive capacities by which humans and perhaps other animals retain information and reconstruct past experiences, usually for present purposes. Our particular abilities to conjure up long-gone episodes of our lives are both familiar and puzzling. We remember experiences and events which are not happening now, so memory seems to differ from perception. We remember events which really happened, so memory is unlike pure imagination. Memory seems to be a source of knowledge, or perhaps just is retained knowledge. Remembering is often covered with emotion. It is an essential part of much reasoning. It is connected in obscure ways with dreaming. Some memories are shaped by language, others by imagery. Much of our moral life depends on the peculiar ways in which we are embedded in time. Memory goes wrong in mundane and minor, or in dramatic and disastrous ways.

Understanding the development of memory milestones

in typically developing children

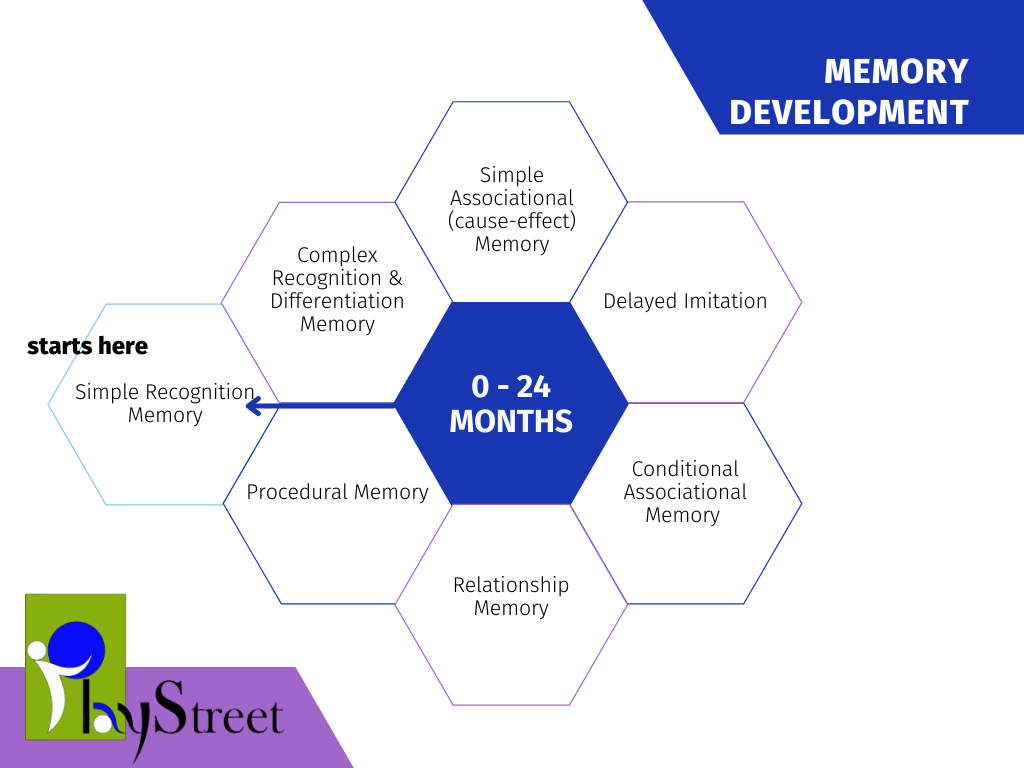

The formation of memory starts as early as in infancy. Memory and Delayed Imitation are interconnected. The typical memory development in a typically developing child is as follows:

0-24 months – Developing co-regulation and memory

Let’s find how memory is important in development of the relationship and cognitive foundations in children.

- Simple Recognition Memory – This simplest form of memory involves recognizing something we have seen or heard before as familiar to us.

-

Shows recognition of settings, persons, objects tasks and other stimuli that he has seen once before

-

Complex Recognition & Differentiation Memory: It involves recognizing several simple activity frameworks and distinguishes them from each other

-

Simple Associational (cause-effect) Memory – It involves remembering relation of simple actions and immediate consequences. It happens from 3-6 months of age. It includes:

-

Remains in a receptive position following events and actions that have produced a pleasurable response, or where actions have led to successful goal attainment.

-

Motivated to repeat actions that have resulted in an immediate pleasurable response.

-

Seeks to avoid events that have resulted in an immediate negative response.

-

Anticipates repetition of emotions experienced in similar activities

-

Delayed Imitation – It involves performing an observed, but not enacted task after a day’s delay. Research says that it develops at the age of 6 months.

-

Conditional Associational Memory – It is about remembering that certain types of cause-effect relationships are mediated by specific activities, settings persons etc.

-

Associates specific settings with role-actions typically performed in the setting, and persons typically available in the setting

-

Conditional performance (e.g. “Keep doing ‘A’ until you get to this point and then do ‘B’ ” while in a specific setting C

-

Conditional results (e.g. “Keep doing this until you get to this point”) while in a specific setting

-

Relationship Memory – It involves expecting that if partners initiate one of the roles of a familiar complementary role enactment (e.g. sweeping, dustpan holder), in the setting and with the materials that are customary, it is a signal for the child to initiate the second complementary role

-

Procedural Memory – It is about remembering a series of steps, that if applied in sequence, lead to a result, or that fit together to portray an experience.

-

It includes remembering procedures and later use them in a functional manner, when children have been carefully demonstrated by familiar adults

-

Three-step sequences appears to be the minimum number as it represents a starting action, a modification from the starting point and the attainment of a result. (First, I did ‘a’, then I did ‘b’, then I achieved ‘c’). Three steps seem to be a critical number in a sequence because it allows the child to remember an initiation, an enactment and then a completion – the essential requirements for the simplest form of coherent narrative reflection

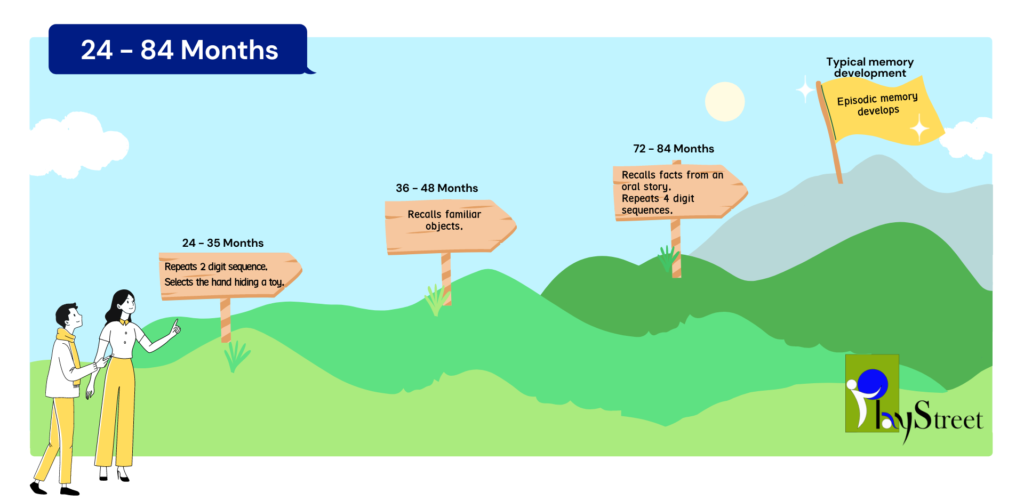

24-35 months

-

Repeats 2-digit sequences

-

Selects the hand hiding a toy

36-48 months

-

Recalls familiar objects

72-84 months

-

Recalls facts from an oral story

-

Repeats 4-digit sequences

How is the memory development different for children with autism?

People on the spectrum can have an excellent Semantic Memory or types of memory that are usually called recognition, associated, cued and procedural memory. This type of memory is encoded as habit memory or a memory that can lead to specific goal. It can also be used for instrumental interactions – such as a scripted action or a rote reaction even when presented with a novel and different stimuli. This is a very predictable sort of memory that can expand the number of facts but not the emotions that are behind an interaction or a memory.

Another type of memory, called Episodic Memory or Autobiographical Memory can present a lot of difficulty to people on the spectrum. This type of memory also involves the use of a different neurological circuit. Specifically, the circuit involved follows a pathway from the pre-frontal lobes (executive functioning) to an area called the Limbic System. The Limbic System (primarily in the middle of the brain) is a series of inter-related structures that play a key role in emotion, motivation and integrates information from sensory areas as well as the brainstem. Structures in the Limbic System, work in co-ordination and help to regulate autonomic nervous system functions, memory, hormone production/release, neurotransmitter regulation for mood, attention, fear, etc.

The Episodic Memory also helps to give us a sense of self and to have to the ability to reflect back on emotional interactions.

It is important that children the memories to be able to access at a later time. So how do we know if our attempts of working with children with Autism are helping them to encode the right memories and also if those memories are effective?

“Memories = Motivations”, one of the major over-riding objectives of the whole RDI Program is helping our children on the autism spectrum develop a storehouse of Episodic Memories concerning encountering uncertainty and successfully mastering it. In order to help us make sure that it is not “unproductive” uncertainty that is too difficult for a child to master, each stage of the RDI Program has been carefully organized and follows the path of typical development.

“How-to” – Program Tips for Episodic Memory Success

One fundamental thing to remember is that you can’t force someone to have emotions. They have to be the person’s genuine emotions. Start very simply, with establishing the things you jointly have strong reactions to, and sharing them. Also, to get a genuine emotional reaction, make sure there is enough uncertainty (surprise, change, payoff, etc.) to provoke it.

Individuals on the spectrum have difficulty experiencing emotions when they are overloaded, so simplify the environment if this is an obstacle, and allow lots of processing time. A good general rule is to provide twice as much time as you think you need.

How to know if memory encoding has been successful

A memory has been encoded successfully if your children’s actions demonstrate they are aware of the elements you are spotlighting and if those elements are perceived as the highlight of the actions, you are doing together. Here are some practical suggestions for you to test this:

-

Observe if your emotional expression matters to your child: whether children notice if you have an amplified emotional expression or no emotional expression at all. For example, to determine if you’re important to the emotional response or not, try looking bored, (or afraid or disgusted) and see if your child continues to laugh. If your child doesn’t notice or care about the change in your emotional state, you will need to revise your means of spotlighting so he or she understands it is the relationship which creates the enjoyment, and not the procedure.

-

Take note of how your child reacts when doing photo or other memory reviews. Notice if your child looks like he’s re-experiencing the emotion and communicates a desire to do the activity again. If your child is verbal, notice if he or she makes comments like, we had fun. Can we do it again? or says things which indicate a more procedural memory, like, that was on Tuesday at Grandma’s house. It was raining that day.

-

For both non-verbal and verbal children alike, you can offer the choice of repeating an activity without the key element that made it enjoyable, like the other person. For example, if you are running and falling onto beanbags together and spotlighting the shared anticipation just before you fall, offer your children the chance to run and fall without you and see if they notice or care. If your child prefers to do the activity alone, it means they didn’t encode the memory in the way you wanted them to, and they missed the point.

Tips to make sure the memory itself does not become rigid or procedural

Once you know a memory has been successfully encoded, you will want to make sure it stays flexible and open to re-encoding:

Point out similarities between two different memories, for example, “This is just like the thing we saw last time.”

Create several different memories of the same activity or same place.

When reviewing photos, videos or other representations, at first you might use the same short “label,” to trigger the memory, but vary the other language or non-verbal communication so the review does not become rote.

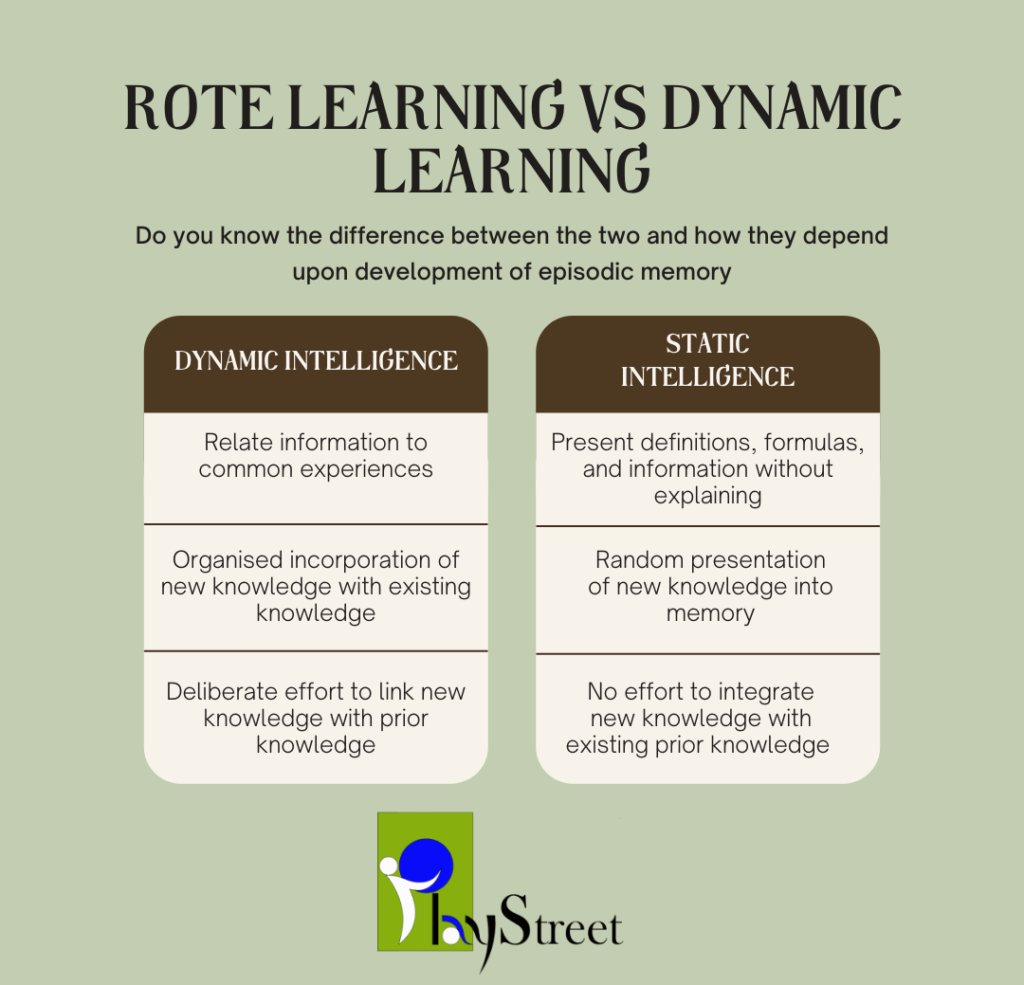

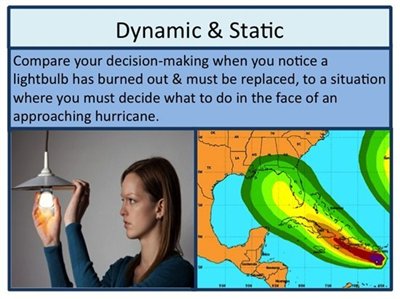

Static vs Dynamic intelligence

When we are in a static world, things are either similar to one another or they are different and we are able to operate that way, as we can say that a concept or a category is similar or not. Its about remembering the facts and recall them from memory.

We live in a complex and dynamic world where every day we must solve problems, make decisions and face challenges. Dynamic Intelligence is the term we use to describe the mental functioning that enable humans to successfully navigate this world and our relationships.

In the dynamic world they are similar and different at the same time.

In a dynamic world we can’t tell that how much is similar and how much is different, but we analyze them as things keep changing, some things continue the way they are and some do not. Some things which were similar before will not be similar next time.

We are living in a world that is partially knowable and partially not knowable.

In static world it means that we task our problems, like we sleep, we eat. So, we know things, we know that we are able to do them or we are not able to do them.

But in the dynamic world we have both, knowing and not knowing at the same time. There is no way to know what is going to happen next as there are many variables involved but we still proceed. In other words, the action we take we can’t know exactly what we are going to do.

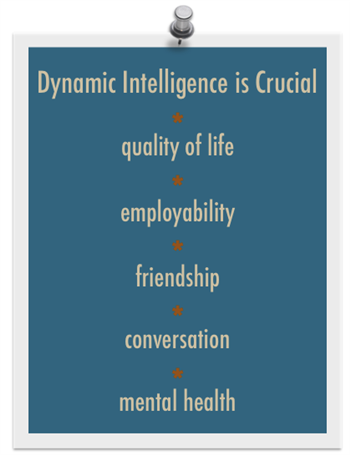

Dynamic Intelligence is crucial to life as we know it, especially in the areas that affect our quality of life; employability, friendship, conversation and mental health.

Mindful Decision-Making

Most experts believe that our ability to make complex decisions and the sophisticated, integrated dynamic neural structure that has evolved to support decision-making, is the ultimate achievement of human evolution. Compared to other species, we are undoubtedly the champions when it comes to effective decision-making in complex, uncertain, dynamic environments.

We use the term ‘Mindful Decision-Making’ to refer to an intentional, thoughtful process used when navigating through mentally challenging environments that is flexibly, creatively and adaptively attuned to the dynamically changing circumstances we encounter.

Find solutions that are good-enough to meet the needs of the situation, rather than trying to be perfect.

Adept at handling problems that do not seem to have right or wrong solutions

Makes complex decisions by looking for a response that is a ‘best-fit’ with multiple variables

Conclusion:

Children diagnosed with Autism have strong rote memory leading to greater static intelligence and thus they can remember huge facts about the subjects they are interested in. On the other hand, they have severe deficits in dynamic intelligence due to the difficulty in foundations of developing episodic memory because if which children with Autism have difficulties in forming social relationships, rich and pragmatic language usage and flexible lifestyle.

Working on the foundations of human development is more important in Autism remediation compared to teaching static skills to children, as quality of life depends on using the dynamic and meaningful learning to form meaningful relationships.

References:

0 Comments