Many of us relate academics to reading and writing and assume that these are skills that our children pick up once they start preschool or schooling. But there are foundations that children build much more naturally much earlier that tend to go overlooked.

A very important foundation that is related to the development of academics is spoken language. Yes, you read that right. Spoken language is the foundation for the development of literacy skills. The experiences gained while talking and listening as toddlers and during preschool years prepare children to read and write.

Language development refers to children’s emerging abilities to understand and use language. Language skills are receptive (the ability to listen to and understand language) and expressive (the ability to use language to communicate ideas, thoughts, and feelings). Children’s language ability affects learning and development in all areas, especially emerging literacy.

Emerging literacy refers to the knowledge and skills that lay the foundation for reading and writing. For infants and toddlers, emerging literacy is embedded in the Language and Communication domain. There is a fundamental and reciprocal relationship between oral language (listening and speaking), written language, and reading. Initially, reading and writing are dependent on oral language skills. Eventually, reading and writing extend the oral language.

Spoken language competence involves several systems. Children must master a system for representing meaning, and acquire a facility with the forms of language, ranging from the sound structure of words to the grammatical structure of sentences. This knowledge of language must be paired with social skills. Most of this understanding and learning happens in the natural environment and happens without any formal instruction.

A few of the components of language that play a very important role are:

- Phoneme awareness – the ability to attend to, think about, and work with the individual sounds in words

- Phonics – the relationship between the sounds and written symbols of language or phoneme-grapheme correspondence

- Fluency – the ability to read text quickly and accurately

- Vocabulary – the ability to understand the meanings of the words we use to communicate

- Comprehension – the ability to derive meaning from what is read, which is the reason for reading

The connection of these components to literacy skills are:

- Reading – Poor instruction in phonemic awareness and phonics is the most common reason why students exhibit reading problems. It can also be caused by breakdowns in fluency, vocabulary, and/or text comprehension.

- Writing – The skills required for effective writing include knowledge of spelling,

capitalization, punctuation, and grammar, an understanding of how word order in sentences affects meaning, and the ability to distinguish main ideas from supporting ideas or details.

capitalization, punctuation, and grammar, an understanding of how word order in sentences affects meaning, and the ability to distinguish main ideas from supporting ideas or details. - Listening involves understanding what we hear. To listen effectively, one must be able to retain “chunks” of language in short-term and working memory, recognize and understand vocabulary, recognize the stress and rhythm patterns of speech and glean meaning from context.

- Speaking skills include the correct pronunciation of words, the appropriate use of vocabulary and grammar, and the ability to recall words from long-term memory.

Preschool children begin to develop some awareness of this knowledge by rhyming words, for example, or taking a word apart into syllables. Early reading development in alphabetic languages such as English depends on the integrity of phonological awareness and other related phonological processing abilities.

Learning to read also requires several skills such as word recognition and comprehension. Early in reading development, children need to recognize letters, be aware of and able to manipulate sounds within words, and use conventions about the relationship between letters and their pronunciation. In addition, the child needs to be able to interpret the meaning of the printed text.

Learning to read also requires several skills such as word recognition and comprehension. Early in reading development, children need to recognize letters, be aware of and able to manipulate sounds within words, and use conventions about the relationship between letters and their pronunciation. In addition, the child needs to be able to interpret the meaning of the printed text.

Children who struggle with language often perform poorly in school because they have trouble understanding what is said to them, and what they read, and expressing their thoughts to others. Hence, it is very important to be able to understand this connection to be able to identify and assess and provide appropriate intervention for the same.

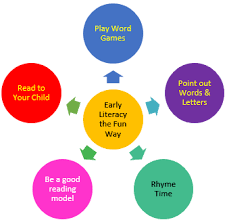

How can we as parents and professionals ensure early language intervention and stimulation to facilitate emergent literacy skills?

- “Children learn the words that they hear most.”

Children learn language through listening and speaking to adults and peers. Children will learn the languages that they hear the most. Using many words and many types of words in each of a child’s languages builds their vocabulary and supports their overall language development. - “Social interaction matters.”

Children learn not only by hearing language, but by engaging in conversations with responsive adults. Adults who engage children in conversation (whether cooing back and forth with a baby or extending talk about the afternoon’s activities with a preschooler) support their language development. Hearing words, even if presented in an interesting format like television, does not guarantee language learning will take place. - “Children learn words for things and events that interest them.”

Children are more likely to learn the language when you talk about things they’re looking at or focused on. They also learn when you respond to their attempts to communicate, including gestures and facial expressions. Providing children with stimulating experiences, and then talking about those experiences, supports children in learning language.

Children are more likely to learn the language when you talk about things they’re looking at or focused on. They also learn when you respond to their attempts to communicate, including gestures and facial expressions. Providing children with stimulating experiences, and then talking about those experiences, supports children in learning language. - “Children learn words best in meaningful contexts.”

Learning a new word while acting it out in an activity, or hearing the word used along with other users as part of a thematic exploration, provides children with lots of information about the new word that can help them to learn and remember it. - “Oral vocabulary is very important to reading comprehension; readers need to know the meanings of individual words to understand the text as a whole.”

Be careful not to close off conversations by telling children to be quiet, ignoring their attempts to communicate, or correcting their “mistakes.” Rephrasing is much more effective at supporting children’s language development than “correcting” them. For example, if a child says, “I done-d that,” an adult might reply, “Oh, you did that?  Incorporate books and reading into daily routines, like a part of a child’s bedtime ritual.

Incorporate books and reading into daily routines, like a part of a child’s bedtime ritual.

Remember that very young children may not have the attention span to sit through long books; reading a book partially is still helpful. Use all forms of verbal expression to read to children, including reading, singing, and conversing about the content of books. Connect the stories found in books to the child’s life (i.e., personalize them).

REFERENCES

-

- https://www.languagemagazine.com/5100-2/

- https://www.child-encyclopedia.com/language-development-and-literacy/according-experts/literacy-outcome-language-development-and-its

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/20205005?seq=1

- https://www.kennedykrieger.org/stories/linking-research-classrooms-blog/language-literacy-connection-understanding-basics-help-students-succeed

- https://www.universalclass.com/articles/psychology/child-development/language-and-literacy-development-in-understanding-child-development.htm

For more information from our previous blogs

0 Comments