It is not always the case that a child with a history of speech and language difficulties should have literacy problems. But if these speech difficulties persist beyond 5 years of age, there is a higher risk of developing associated difficulties in reading, spelling and sometimes maths. Many parents wonder if their young child with apraxia of speech (verbal dyspraxia) will go on to experience difficulties in their education . While there is no certainty that literacy problems will or will not develop, there is research that has shown that children with spoken language problems are at higher risk for literacy related problems.

WHAT GENERALLY HAPPENS?

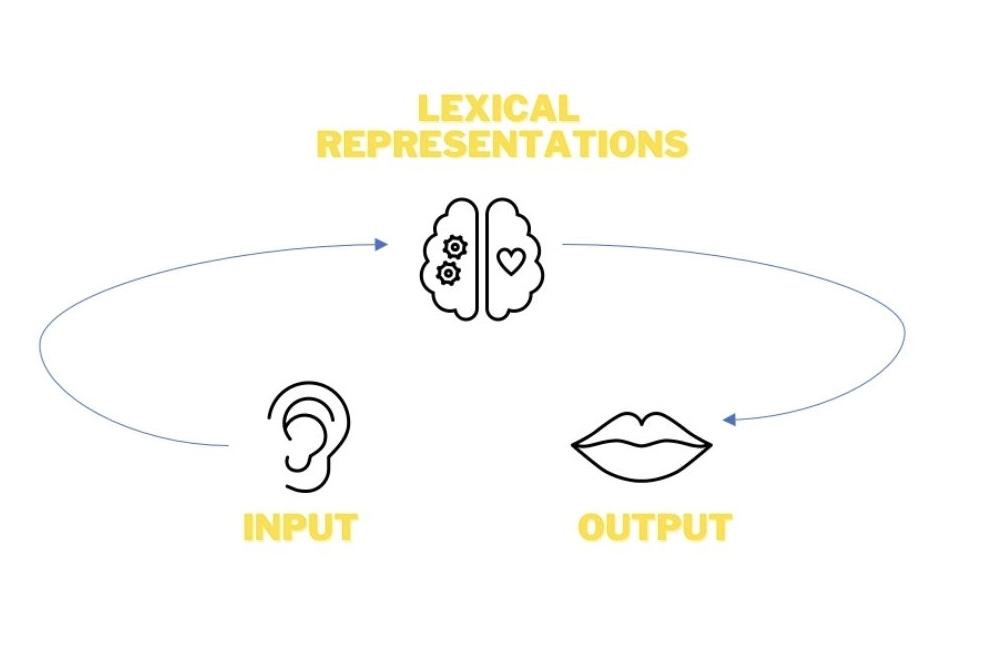

We hear words or spoken information through our ears (input), which is processed and stored in a word store (lexical representations), and then accessed and programmed for speaking (output) when we need to use or express this information.

However for some children with speech difficulties, the following could happen:

- Difficulty with differentiating between similar sounding words (i.e. difficulty with speech input)

- Imprecise or “fuzzy” storage of words which makes it difficult to access them (word finding difficulties)

- Poor or unclear production of these words because of missing elements in the word store

- Poor pronunciation of these words at an articulatory level (even though they know the words very well).

When there are persisting difficulties, all of the above could get affected, which could also lead to language difficulties (comprehension and/or expression).

The speech processing system, as illustrated above, is not only the basis for speech and language development but also the foundation for literacy development; ‘written language’ being an extension of ‘spoken language’.

For example, if a child has delayed understanding of spoken language she/he will find it very hard to access meaning from the printed word even though she/he may be able to decode the letters perfectly well. Sometimes, children with comprehension difficulties are described as ‘hyperlexic’; this term indicates that a child can read print mechanically better than they can understand it. Other children, particularly those with persisting speech difficulties, have a problem with the mechanics of reading and are more likely to be described as ‘dyslexic’ or as having ‘specific’ reading and spelling problems. This suggests a problem at one or more levels in the speech processing system depicted earlier.

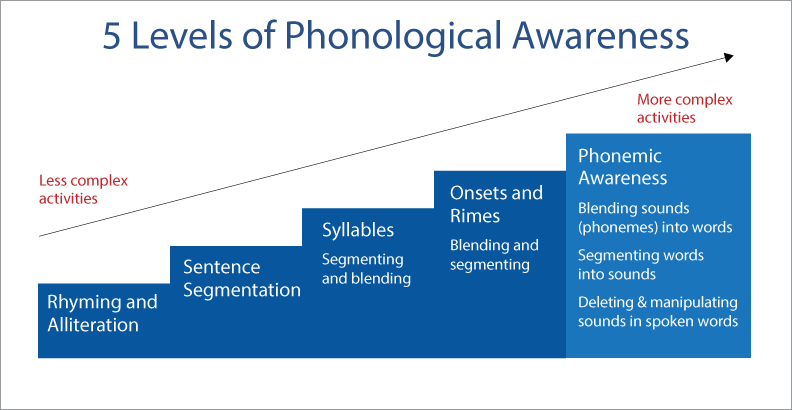

Children with spoken language problems may have difficulty developing what are called phonological awareness skills. Professor Joy Stackhouse, a speech and language therapist, chartered psychologist and teacher of children with specific literacy difficulties, has described phonological awareness in this way:

“Phonological awareness refers to the ability to reflect on and manipulate the structure of an utterance (e.g., into words, syllables, or sounds) as distinct from its meaning. Children need to develop this awareness to make sense of an alphabetic script, such as English, when learning to read and spell. For example, children have to learn that the sounds (phonemes) in a word can be represented by letters (graphemes). When spelling a new word, children have to be able to segment the word into its sounds before they can attach the appropriate letters, and when reading an unfamiliar word, they have to be able to decode the printed letters back to sounds.” (Stackhouse, 1997, p.157)

Phonological awareness is made up of many related skills including: recognition and production of rhyme; identification of number of syllables; sound to word matching, word to word matching; sound deletion; and sound segmentation.

Research has found that a strong predictor of literacy development is phonological awareness. When children demonstrate difficulty with phonological awareness, as do many children with spoken language problems, they are at higher risk of difficulty in literacy related skills like reading and spelling. Stackhouse writes that, “Although recent work has clarified how visual deficits may also affect reading performance, there is an overwhelming consensus that verbal skills are the most influential in literacy development (Catts, Hu, Larrivee, & Swank, 1994).” (Stackhouse, 1997, p. 163)

READING DIFFICULTIES

Children with apraxia of speech or verbal dyspraxia may have difficulty making the jump from the direct to indirect route in reading acquisition.

Children with apraxia of speech or verbal dyspraxia may have difficulty making the jump from the direct to indirect route in reading acquisition.

What does that mean?

Children first develop sight vocabulary – words that they can identify purely by looking at the whole word. This can be described as the direct route. Later, children learn phoneme – grapheme correspondences (sound-letter correspondences) and learn strategies for sounding out words they are trying to read. This can be described as the indirect route. It is important for children to develop this indirect route because if they do not, their reading only progresses to the limits of their visual memory. If they don’t learn phonological strategies via the indirect route then when they are attempting to read an unfamiliar word they will have difficulty decoding the printed letters back to sounds.

Jordan Christian, a self-advocate of Verbal Dyspraxia and an author, in his site “Fighting for my Voice: My life with Verbal Apraxia”, talked about the following:

“I grew up being behind on reading. I would often look at words and attempt to pronounce them. However, I couldn’t pronounce the words yet. I was also unable to make some of the sounds individual letters make. With this being said, while I couldn’t pronounce the words I was trying to read, I couldn’t comprehend what the word originally was. If I was unable to vocalize what each letter sounded like, I was unable to spell words. When I would be asked to spell a word, I would write down what in my mind makes sense, or at least, my best guess. On paper, if you asked me to spell the word ‘delicate’, I may have spelled it like ‘dpcgute’.”

SPELLING DIFFICULTIES

Clear and consistent speech production is particularly important for spelling or when learning new vocabulary. If children are not able to produce the right number of syllables in the word or if they cannot say the word in the same way on more than one occasion then they cannot spell it correctly or store it clearly. Spelling can also be a persisting problem for children who appear to have resolved their speech difficulties, though not to the same extent as those with persisting speech difficulties.

Here are some indicators of a child with apraxia of speech or verbal dyspraxia having difficulties:

- Difficulty progressing from reading words as visual wholes to breaking the words down into their sounds.

- Difficulty with segmenting the word into syllables and syllables into sounds (Spelling attempts may seem bizarre)

- Difficulty in rhyme detection and particularly, rhyme production.

- Difficulty with sound blending.

WHAT CAN BE DONE?

Complete speech and language assessment to assess speech, language and oral-motor abilities; auditory skills (such as auditory discrimination, memory and organization); rhyme detection and production; syllable and phoneme segmentation; reading comprehension and expression; spelling and awareness of reading and spelling strategies. It is also important to include more difficult items in reading and spelling tests (for instance, multisyllabic words) in order to determine a particular child’s difficulty.

Complete speech and language assessment to assess speech, language and oral-motor abilities; auditory skills (such as auditory discrimination, memory and organization); rhyme detection and production; syllable and phoneme segmentation; reading comprehension and expression; spelling and awareness of reading and spelling strategies. It is also important to include more difficult items in reading and spelling tests (for instance, multisyllabic words) in order to determine a particular child’s difficulty.

- Stackhouse suggests the following techniques and activities:

Phoneme-grapheme matched cards (cards with pictures that represent sounds)

Phoneme-grapheme matched cards (cards with pictures that represent sounds)- Color coded systems as visual reminders of language structures or of sound groups

- Sound categorization activities using multi-sensory approaches

Syllable and sound segmentation activities

Syllable and sound segmentation activities- Rhyming work

- Explicit teaching of reading and spelling rules

Home based activities could include:

Home based activities could include:

- Nursery rhymes and rhyme games

- Making games with syllable beats in words

- Drawing attention to the printed word while reading to children

- Using books with rhymes and word patterns

- Music & Movement Therapy – improves speech/language fluency, phonology, working memory, and motor skills by increasing functional neuroactivation, dynamicity of the brain and creating a balanced brain.

In summary, children’s speech difficulties arise from problems at one or more points in their underlying speech processing system. This system is the foundation for their written language as well as their spoken language skills. If this foundation is unstable, additional support will be needed to enable a child to use the strengths s/he has to develop phonological awareness skill and letter knowledge.

References:

- Stackhouse, Joy (1997). Phonological awareness: Connecting speech and literacy problems. In B. Hodson and M.L. Edwards (Eds.), Perspectives in Applied Phonology (pp. 157 – 196). Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen Publications.

- https://www.apraxia-kids.org/apraxia_kids_library/children-with-apraxia-and-reading-writing-and-spelling-difficulties/

- https://fightingformyvoice.com/2020/02/07/reading-writing-and-spelling-difficulties-in-apraxia-my-experience

0 Comments